Archiving 8000 VTuber Songs and Music Covers (and counting) - Part 2: Archiving

Archiving the content with a Worker and Storage

Now that I’ve explained the idea and motivations behind running the archive, how does it actually work? Well first I needed to figure out how to actually save all the content. I’m not exactly proud of the code for the worker since I sort of kept building on top of it which made it a bit of a mess.

The Worker

I decided to mimic the workflow of Ragtag Archive by writing a worker script that’ll download and re-upload the content. I decided that for each individual video I would archive: the video content itself, the thumbnail, and any metadata that already comes with the .info.json which yt-dlp generates.

Sourcing the Videos

Ragtag Archive was already hosting a bunch of VTuber music that doesn’t exist on YouTube, so my priority was to first grab that.

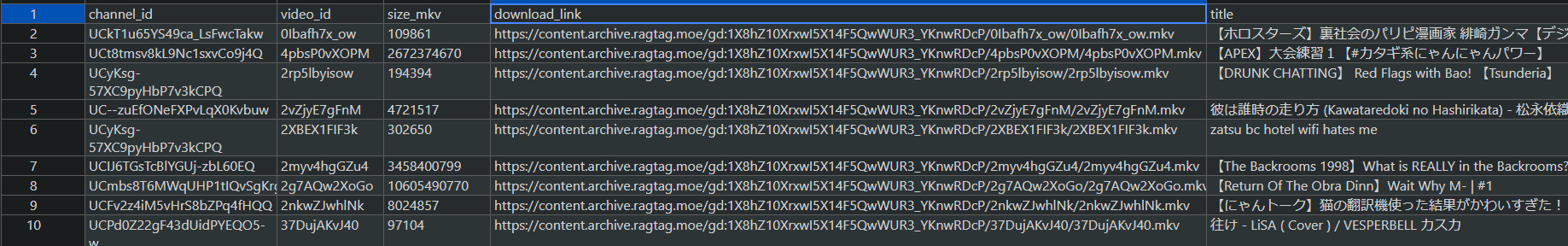

Luckily while they were still about to shut down, they published a dump of the metadata for all the content on Ragtag Archive. From there it was just a matter of finding and saving the video ID of all rows that contain music related keywords (“cover”, “Original song”, “歌てみた”, etc.).

The original dump was a gigantic ndjson, but I decided to turn it into a CSV since the dump of all videos archived on Ragtag but unavailable on YouTube was already in that format, and I wanted to make it more readable in case I needed to manually check things with Excel

Theoretically all I’d need to know was if a given row contained certain keywords, so the only “clean” data I needed to keep was the ID of the video and the direct link to download it from Ragtag (some titles or descriptions could be using the delimiter character resulting in the data being malformed).

def csv_searcher(keywords_title: list, keyword_uploader:str=" ", csv_file: str = "ragtag.csv"):

seen_streams = set()

open('output.csv', 'w', encoding='utf-8', newline='').close()

csv_writer = csv.writer(open('output.csv', 'w', encoding='utf-8', newline=''))

count = 0

for row in get_csv_data(csv_file):

if row[0] == 'channel_id':

continue

title = row[4]

uploader = row[5]

for keyword in keywords_title:

if any(exclude.lower() in title.lower() for exclude in EXCLUDED_KEYWORDS):

continue

if keyword.lower() in title.lower() and

keyword_uploader.lower() in uploader.lower() and

row[1] not in seen_streams:

print(row[4], row[5])

print(row[3])

print("\n")

csv_writer.writerow([row[4], row[5],row[0], row[1], row[2], row[3]]) # This bit me in the ass later

seen_streams.add(row[1])

count += 1

print(count,"results found")I then looked at the few videos identified as “not covers” that were between 1-5 minutes in length to check for any false negatives. Finally, I removed all videos that the script found which were more than 30 minutes long.

After doing that I was left with around 5062 videos. The chances of missing a video that was on Ragtag but not on YouTube are extremely low since I went through the CSV dump of all the content that was on Ragtag but not on YouTube to triple check I had everything I wanted. Even if I didn’t, chances are it would be on YouTube and I could go and grab it later.

The Remaining Videos

Of course Ragtag doesn’t have every single VTuber music and cover archived. Their focus is on archiving the entirety of channels so its only natural that more niche VTubers fall under their radar.

My solution for this was to make use of public YouTube playlists and the Holodex API to source the rest of the videos.

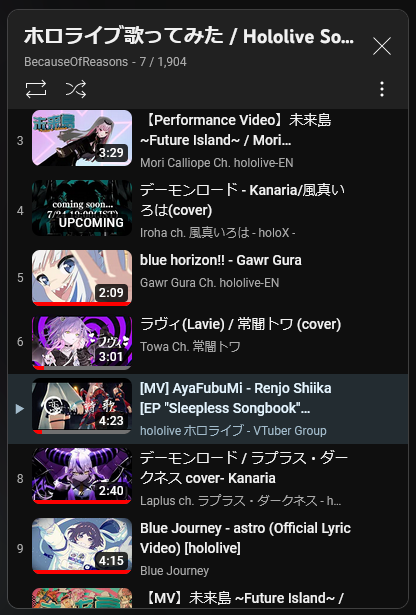

Turns out VTuber fans are pretty dedicated. There are some pretty massive playlists of people adding all the songs and covers by certain subsets of VTubers. For example the one below has 1904 Hololive songs and covers in it.

Grabbing the video IDs from these playlists is pretty easy too with yt-dlp

yt-dlp --flat-playlist -i --print-to-file url playlist.txt "URL"

The final place I searched was over on Holodex. It’s got a pretty nice search feature where you can search through videos by the topics. I’m pretty sure they’re automatically tagged since occasionally you do find one or videos which match certain keywords but are clearly not of that topic.

I used the Music_Cover and Original_Song tags and was able to see 36 videos per page with there being 730 pages meaning they had identified 26,280 potential music covers. Holodex does keep the index of videos that are already deleted or archived, so the actual number of available videos will be a bit less. But nevertheless it’s a pool of covers to work off of.

I used JHolodex API Wrapper to try and grab the URLs for all the videos but ran into a problem around 3000 videos in where the POST request associated with searching returns no data. I think it might be an attempt to avoid potential API abuse?, but at this point I was more eager to just move past the phase of sourcing videos and start archiving them. I grabbed what I could and called it a day.

try {

Holodex holodex = new Holodex(HOLODEX_API_KEY);

for (int i = 0; i < MAXIMUM; i += 50) {

System.out.println("Getting videos from " + offset + " to " + (offset + 50));

List<SimpleVideo> videos = (List<SimpleVideo>) holodex.searchVideo(

new VideoSearchQueryBuilder().setSort("newest").setTopic(List.of("Music_Cover", "Original_Song")).

setPaginated(false).setLimit(50).setOffset(offset));

for (Object video : videos) {

SimpleVideo vid = (SimpleVideo) video;

Video detailedVid = holodex.getVideo(new VideoByVideoIdQueryBuilder().setVideoId(vid.id));

// Now we can record the info we need from the Video object

}

offset += 50;

System.out.println("Sleeping for 2 minutes");

Thread.sleep(120000);

}

} catch (HolodexException ex) {

throw new RuntimeException(ex);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}After doing some deduplication, I was left with around 6500 unique songs and covers. There are certainly more out there but, this is a good start.

Archiving the Content

I ended up opting to write another simple Python script that basically wraps yt-dlp to download the videos. It pretty much boils down to this:

subprocess.run(f'yt-dlp {url}{url_id} -f "bestvideo[height<=1080][ext=webm]+bestaudio" -o "{self._output_dir}/%(id)s.%(ext)s" --add-metadata',shell=True,)Essentially for any video unavailable on YouTube, I would attempt to download it from Ragtag (using the direct links that I had saved from earlier).

I would always try downloading from YouTube through yt-dlp first as Ragtag was being overloaded with people rushing to save content before the day it would shut down.

Ragtag stores videos as .mkv files so once they were downloaded I converted them over to .webm so that videos from YouTube and Ragtag would be in the same format. As far as I’m aware WEBM is a subset of MKV, so it was just a matter of changing the containers.

The metadata for each video was handled similarly. Use yt-dlp to download the .info.json file, if its unavailable then try and get it from Ragtag.

subprocess.run(f'yt-dlp --write-info-json -o "metadata_output/%(id)s.%(ext)s" --skip-download {url}', shell=True)But you don’t have the direct link to the .info.json on Ragtag?

The solution is actually quite simple.

Ragtag’s storage is broken up into a number of TeamDrives with each one hosting a folder containing the contents of a video and all other associated data. The URL they use to host their videos is in this format:

https://content.archive.ragtag.moe/gd:1ujQwfkOSa8_3Im-DSuAGp-oOfsTgj9u3/4VBYfb200Ss/4VBYfb200Ss.mkvThe gd portion of the URL indicates that the video with ID 4VBYfb200Ss is stored on the TeamDrive with ID 1ujQwfkOSa8_3Im-DSuAGp-oOfsTgj9u3. This would then mean that the .info.json for this video would be stored at:

https://content.archive.ragtag.moe/gd:1ujQwfkOSa8_3Im-DSuAGp-oOfsTgj9u3/4VBYfb200Ss/4VBYfb200Ss.info.jsonThumbnails

Thumbnails were handled slightly differently when downloading from YouTube. For those unaware you can access all the versions of thumbnails for a particular video by going to https://img.youtube.com/vi/{VIDEO_ID}/{RESOLUTION} (so long as the video is public).

Downloading thumbnails was just a matter of swapping the video ID and requesting the max resolution thumbnail (maxresdefault.jpg). I kept mqdefault.jpg as a potential backup in case the video does not have a high quality thumbnail available.

A trick of sorts

Now obviously because the data dump from Ragtag is slowly growing out of date, there will come a time when perhaps a video isn’t already downloaded, isn’t available on YouTube, but perhaps is on Ragtag. We no longer have the direct link to the video in a nice CSV format anymore, so how do we download it?

The trick I’ve employed is to keep a list of active Ragtag Drive Bases and cycle through them until the video is found.

- Attempt to download a video from Ragtag using a list of known Drive Bases

- If all Drive Bases have been exhausted, mark the download as failed somewhere in a text file

- Manually download the video using Ragtag’s web interface and make a note of the Drive Base

- Add the Drive Base to the list of known Drive Bases

(I’m sure if I asked nicely enough the maintainers could provide a list too, but this scenario is pretty rare already)

This cycle builds up a list of Drive Bases that are known to have content on them. As you add more Drive Bases to the list, the chances of finding a video on one of them increases.

Here’s an example of this with downloading the thumbnail for a video.

RAGTAG_DRIVEBASES = [

"0ALv7Nd0fL72dUk9PVA",

"0AKRj4mXCkOw1Uk9PVA",

"0AAVHoXgF39eKUk9PVA",

"0ABbPCVFfmTmDUk9PVA",

"0AO49onHihFmaUk9PVA",

"0APcbUqyfMhbLUk9PVA",

"0ANsY3BPG5rJwUk9PVA",

"1ujQwfkOSa8_3Im-DSuAGp-oOfsTgj9u3",

"1LvMYR3gmXPLzseeMnaMCW40Z1aKT3RJi",

"1icHsiMjYCoBs1PeRV0zimhcEfBgy-OMM",

]

def download_thumbnail_yt(video_id: str):

if not os.path.exists("thumbnails"):

os.makedirs("thumbnails")

try:

url = f"https://img.youtube.com/vi/{video_id}/maxresdefault.jpg"

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, f"thumbnails/{video_id}.jpg")

print("Successfully downloaded thumbnail from YouTube (Maxres)")

return True

except Exception:

print("Error downloading thumbnail from youtube (Maxres)", video_id)

try:

url = f"https://img.youtube.com/vi/{video_id}/mqdefault.jpg"

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, f"thumbnails/{video_id}.jpg")

print("Successfully downloaded thumbnail from YouTube (MQ)")

return True

except Exception:

print("Error downloading thumbnail from youtube (MQ)", video_id)

for drivebase in RAGTAG_DRIVEBASES:

url = f"https://content.archive.ragtag.moe/gd:{drivebase}/{video_id}/{video_id}.jpg"

try:

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, f"thumbnails/{video_id}.jpg")

print("Successfully downloaded from Ragtag Drivebase", drivebase)

return True

except Exception:

print("Failed to download from Ragtag Drivebase:", drivebase)

if not os.path.exists("error_thumb.txt"):

open("error_thumb.txt", "w", encoding="utf-8").close()

with open("error_thumb.txt", "a", encoding="utf-8") as error_thumb_file:

print("Failed to download thumbnail:", video_id)

error_thumb_file.write(video_id + "\n")

return FalseBilibili and Other Sites?

One thing that Ragtag does not archive is Bilibili content. One of the largest VTuber companies, Nijisanji, also has a Chinese branch known as VirtuaReal who upload on Bilibili rather than YouTube.

Turns out because I was already using yt-dlp, it was pretty simple to add support for Bilibili. I wrote a nice little abstract class which serves as the “archiving protocol”. Since yt-dlp is already highly configurable, it wouldn’t be hard to add even more sites in the future.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

import os

class VideoDownloader(ABC):

def __init__(self, output_dir: str,

log_skip_file: str = "logs/skipped.txt",

log_deleted_file: str = "logs/deleted.txt",):

self._LOG_SKIP_FILE = log_skip_file

self._LOG_DELETED_FILE = log_deleted_file

self._output_dir = output_dir

def _make_files_and_directories(self):

"""

Makes the necessary files and directories for the downloader to work.

"""

if not os.path.exists(self._LOG_SKIP_FILE):

os.makedirs(os.path.dirname(self._LOG_SKIP_FILE))

with open(self._LOG_SKIP_FILE, "w") as f:

f.write("")

with open(self._LOG_DELETED_FILE, "w") as f:

f.write("")

if not os.path.exists(self._output_dir):

os.makedirs(self._output_dir)

@abstractmethod

def download_urls(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def download_thumbnail(self):

pass

@abstractmethod

def download_metadata(self):

passI was able to grab the video, thumbnail, and metadata all using yt-dlp

subprocess.run(f'yt-dlp {video_url} --write-thumbnail --no-download -o "thumbnails/%(id)s.%(ext)s"', shell=True)

subprocess.run(f'yt-dlp {full_url} -f "bestvideo[ext=mp4]+bestaudio" -o "{self._output_dir}/%(id)s.%(ext)s" --add-metadata --cookies{self._cookies}',shell=True)

# Metadata download is the same as YouTubeI should mention that you do need to provide cookies to yt-dlp in order to download at 1080P since Bilibili locks 1080P playback behind registering for a free account, and 1080P high bitrate + 4K behind a paid subscription.

Interestingly, the only format available is mp4. I ended up deciding to convert all of them to webm after downloading since it’s not only a more efficient format for streaming, but also keeps all the video content in the same format.

This was basically just running an FFMPEG command on all videos in the directory after they were downloaded. It did cause a slight problem later on…

subprocess.run(f"ffmpeg -i {directory}/{file} -c:v libvpx-vp9 -crf 30 -b:v 0 -c:a libopus {directory}/{file.split('.')[0]}.webm", shell=True)So that’s pretty much the basic rundown of how the worker works. There’ll be more bits and pieces here and there to discuss but for the most part this is the gist of it. You’re welcome to peruse the code, it’s a bunch of stuff mushed together but it somehow all works.

Hosting the Workers

I’m not really into the idea of leaving my PC on 24/7 and have it chew at my bandwidth all day, so I decided to host my workers through cloud computing.

I thought about my options and decided to go with DigitalOcean’s Droplets since I had some free credit lying around, and you can run them for as little as $4 a month. Their free outbound bandwidth is also generous with the lowest tier offering 500GB per month.

I’ve opted for running the 1 GB Memory, 1 Intel vCPU droplet, however you can probably make-do with the cheapest option as well.

Now this works great for YouTube videos since there’s practically no CPU or RAM usage when it comes to running the worker script since its just downloading and uploading data. The trouble comes when trying to download and convert Bilibili videos.

Yep. 100% CPU usage. Turns out FFMPEG can be pretty CPU intensive, the process of getting those videos converted to WEBM runs at around 0.05x for me, meaning that a 5-minute video will take around 500 minutes to convert. The solution would be to upgrade the specs of the worker, but that would mean paying more money.

I ended up just making do with the speed. Bilibili isn’t exactly a priority for me either, so I’m fine with it taking a while to download and convert videos. (The entire worker flow is queue based too, I’ll touch on this another time)

Speed

I run 2 workers, both of which pull from the same queue of videos to download. With the current setup, I’m able to average around 3 videos per minute (180 videos per hour) for YouTube videos. Obviously if Bilibili videos are in the queue, the speed will be much slower.

That’s all for now

That’s all I got to say about how I initially sourced content and how the workers archive it. In the next part I’ll get more into the details regarding storage and serving the content.